The story of Candy comic

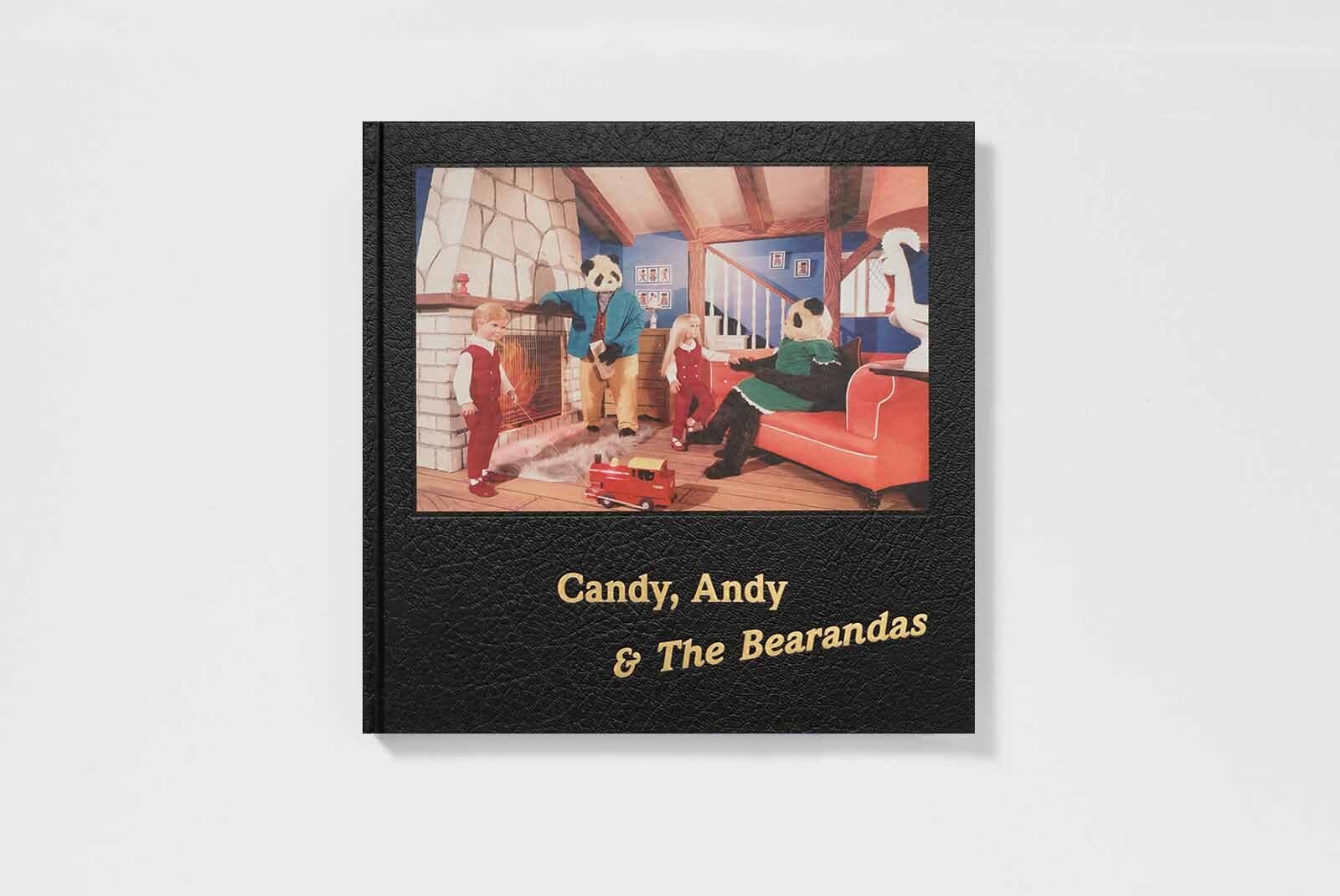

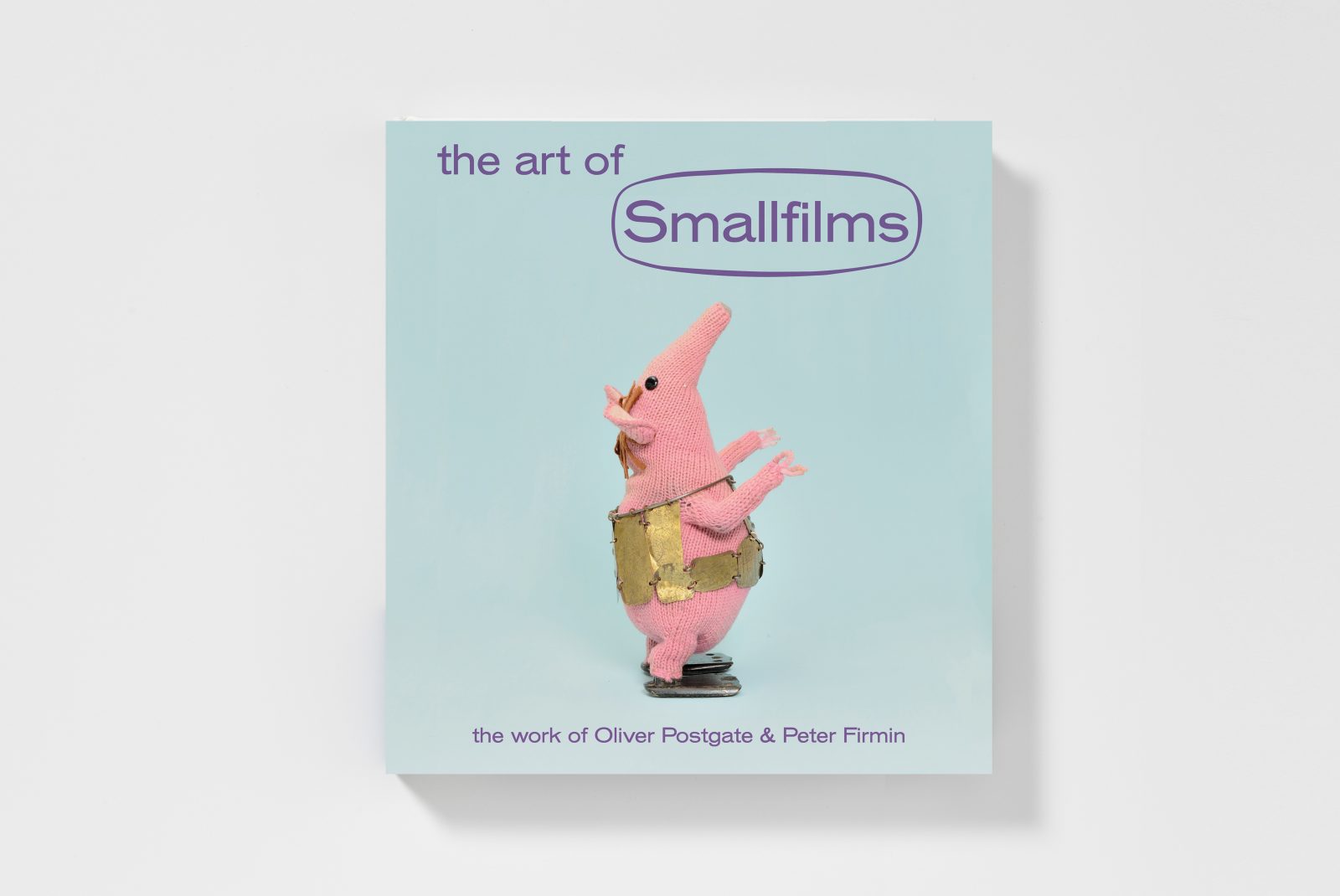

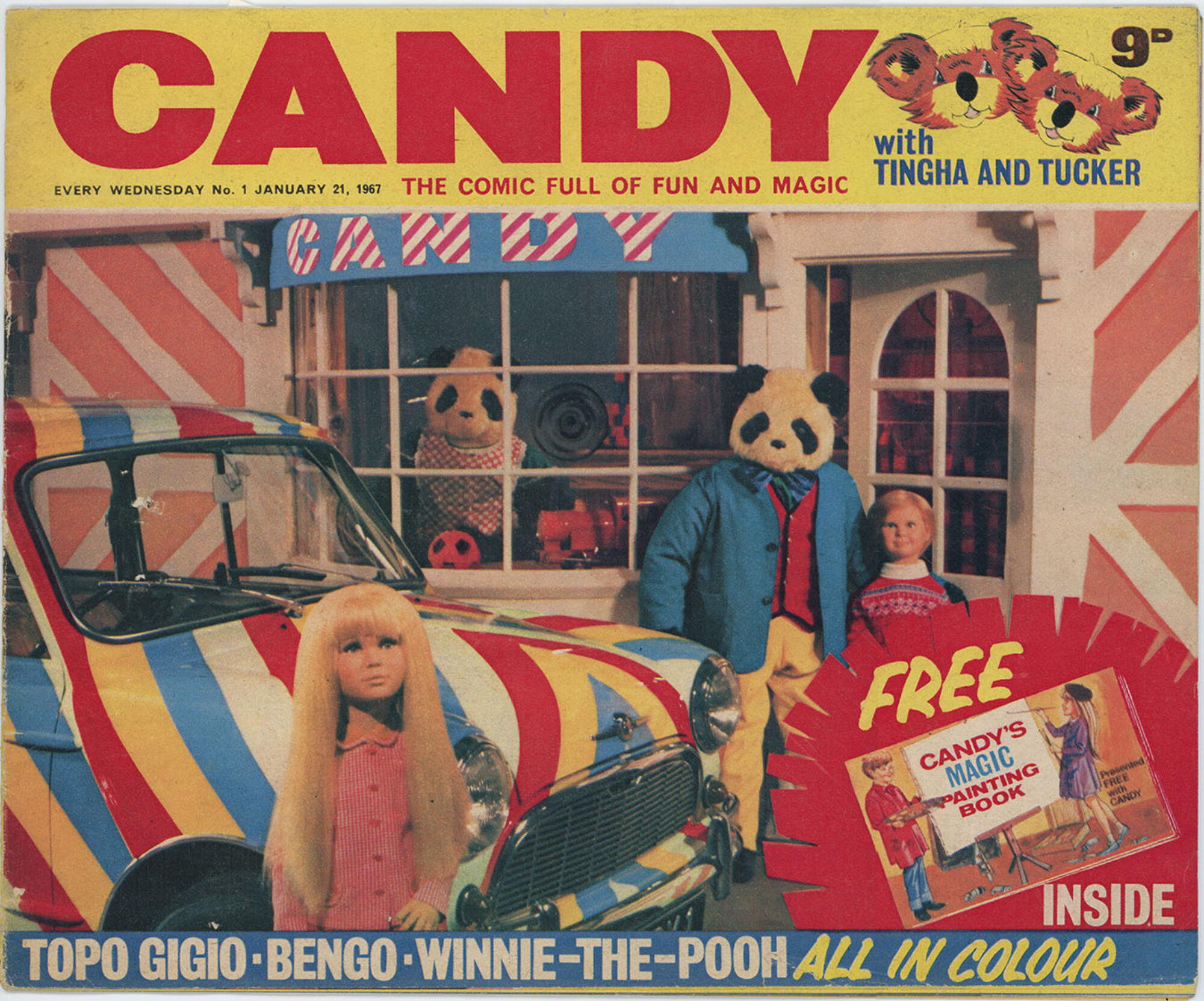

On 21 January 1967, just one month after the final episode of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s Thunderbirds had aired on British television, Candy appeared on the newsstands. A half-page advert in that week’s Daily Mirror proclaimed ‘today’s greatest creators of entertainment for children present a new comic for 3- to 7-year-olds’. The publication is hailed ‘New in every way – Look, Shape, Colour, Content’. There’s even an endorsement from Val Singleton, star presenter of BBC TV’s Blue Peter programme: ‘Your children will love it. You’ll want them to read it’. This all sounds like typical fanfare for a new product in a crowded and competitive market place. However, that nine penny purchase is in my opinion - and I’d wager this goes for just about anyone else who has ever come across Candy - the most bizarre experiment in the history of this nation’s long and illustrious comic book output. For Candy, and her brother Andy, are two ultra realistic life-sized dolls of a boy and a girl who live with Mr and Mrs Bearanda, two giant bipedal panda bear adults in human clothing. Not in the far-flung space age, but in the here and now, in a cosy English village called Riverdale.

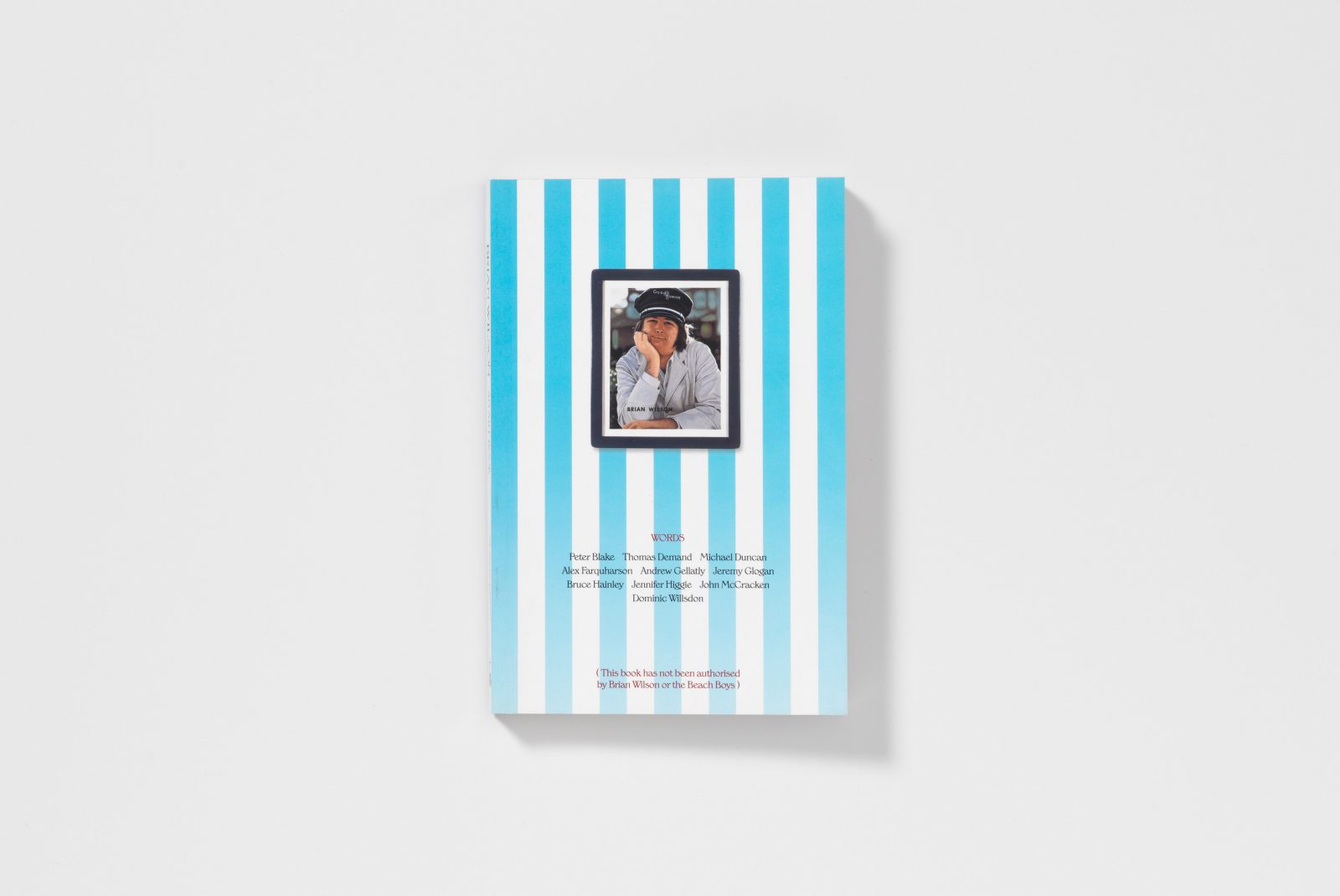

There’s an awful lot of comic book history and beloved titles to choose from since the Victorian days of Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday, Comic Cuts and Illustrated Chips. As we turn the newsprint pages of the 20th century, it’s likely that most youngsters across the land would have heard of The Rainbow, The Dandy, The Beano or The Eagle with their pen and ink drawn stars – Tiger Tim, Desperate Dan, Minnie the Minx, Dan Dare and the Mekon. Into the 1960s, the Anderson’s Century 21 productions responded to the young readers thirst for fresh titles - and given their extraordinary ingenuity, they’d do it brilliantly. TV Century 21, with its cover date set exactly one hundred years on from its 23rd January 1965 issue, instantly tantalised the imagination of a new generation of readers. This was the television-reared set, captivated by the Anderson’s puppet shows like Fireball XL5 and Stingray filmed in ‘Supermarionation’. The inspired combination of photographic stills from the TV series and tabloid newspaper-like copy are now etched into pop culture history. Within, weekly comic strips of the Anderson’s space age shows were dramatically illustrated with eye-popping colour brushstrokes bringing a new visual element to accompany those TV programmes then only seen on black and white television sets. A year on, in January 1966, TV Century 21 gained a sister. Lady Penelope comic, named after the stylish and aristocratic secret agent in Thunderbirds, was aimed at the girls’ market with a frothy mix of pop music, fashion and comic strips. It was edited by a former newspaper journalist Gillian Allen who clearly must have had a massive input into the creation of the most obscure episode in the Sixties heyday of Century 21. But more of that later…

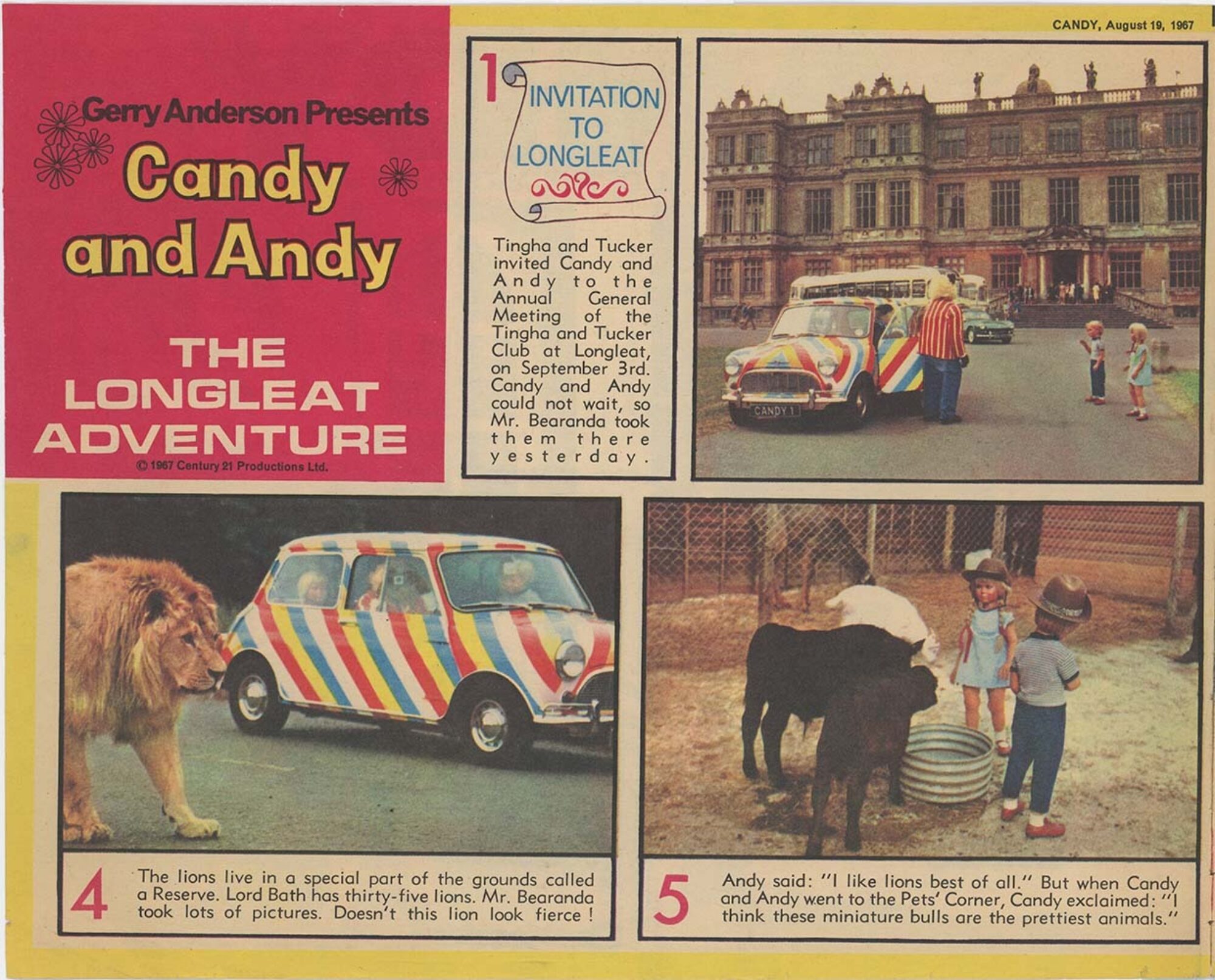

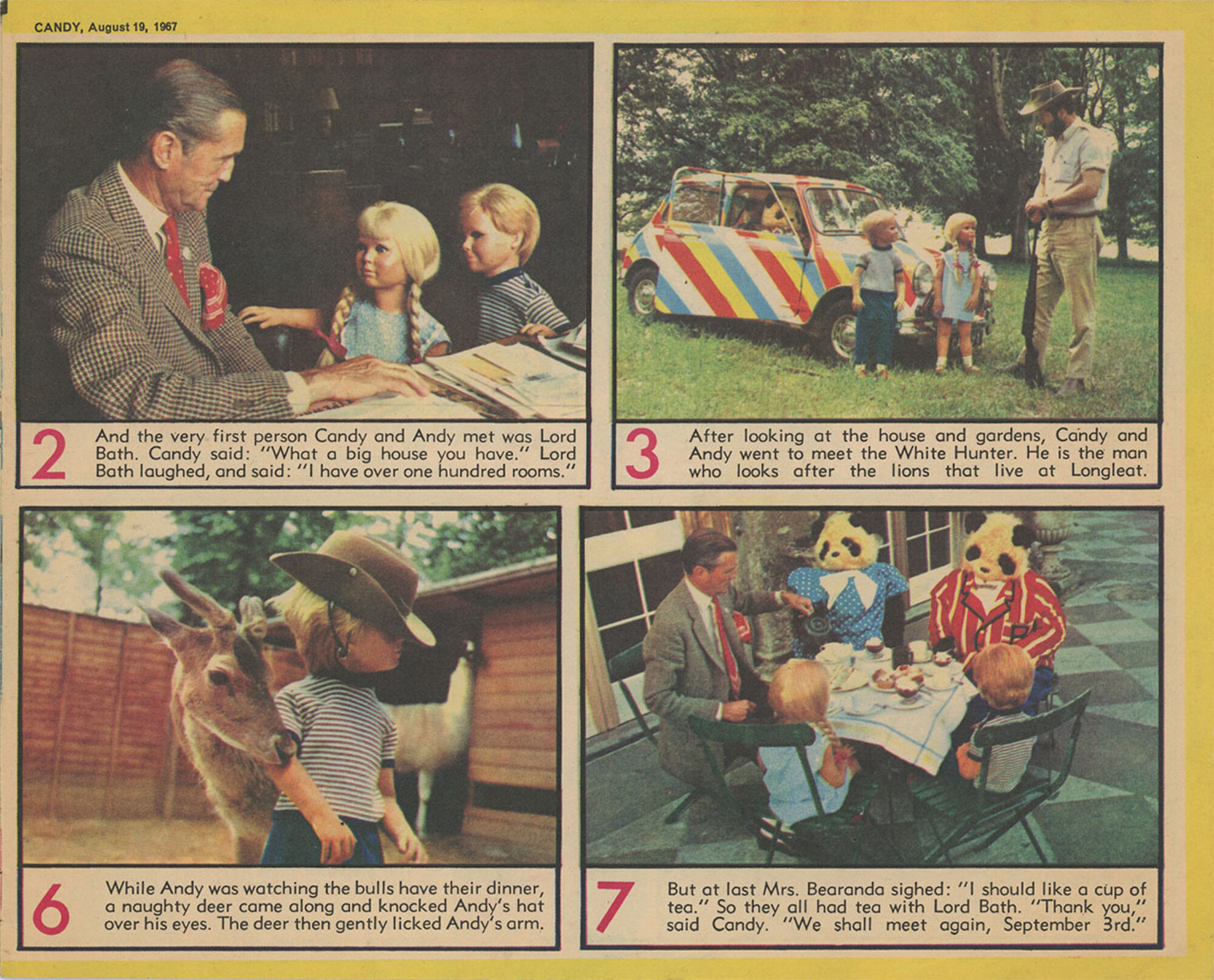

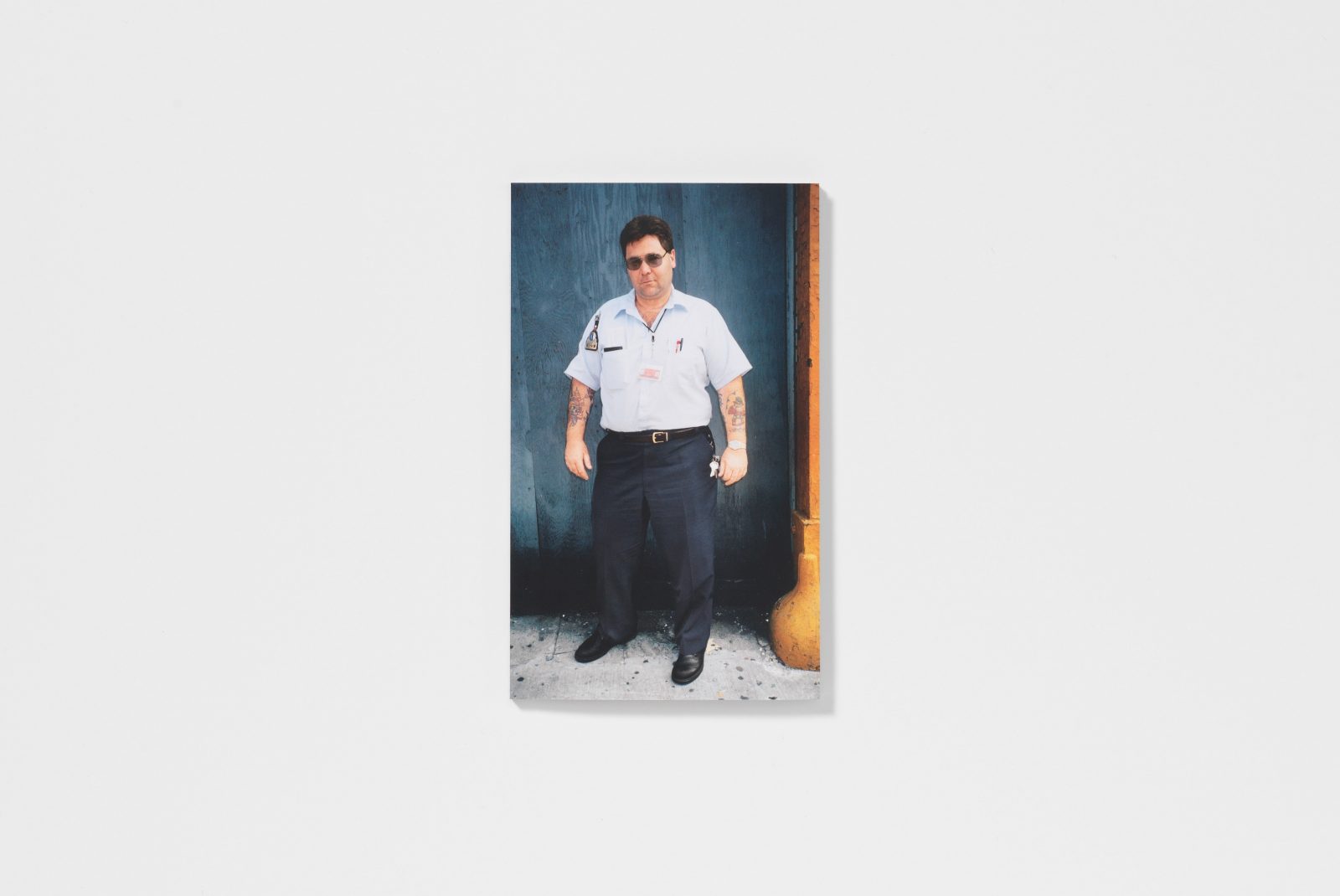

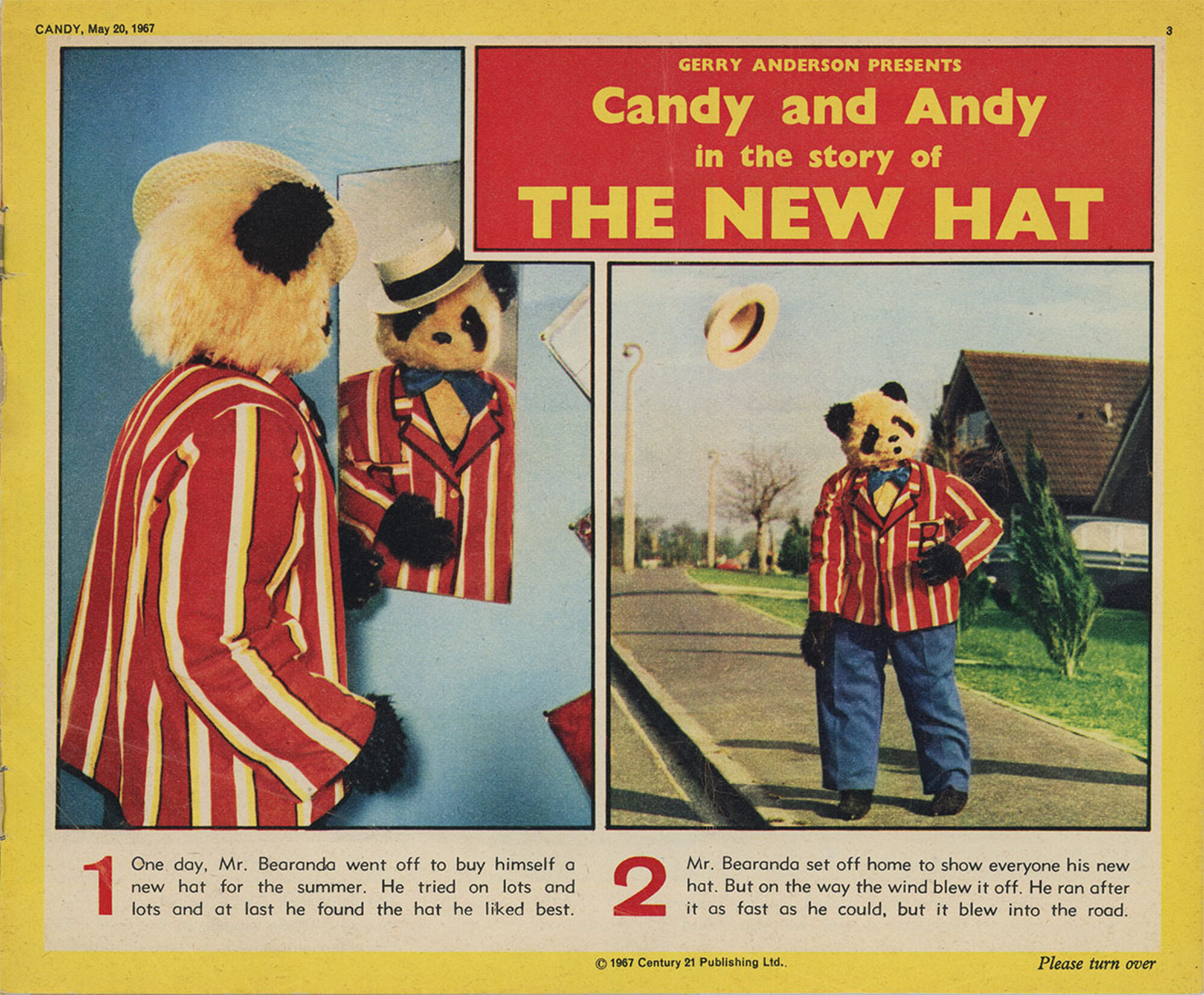

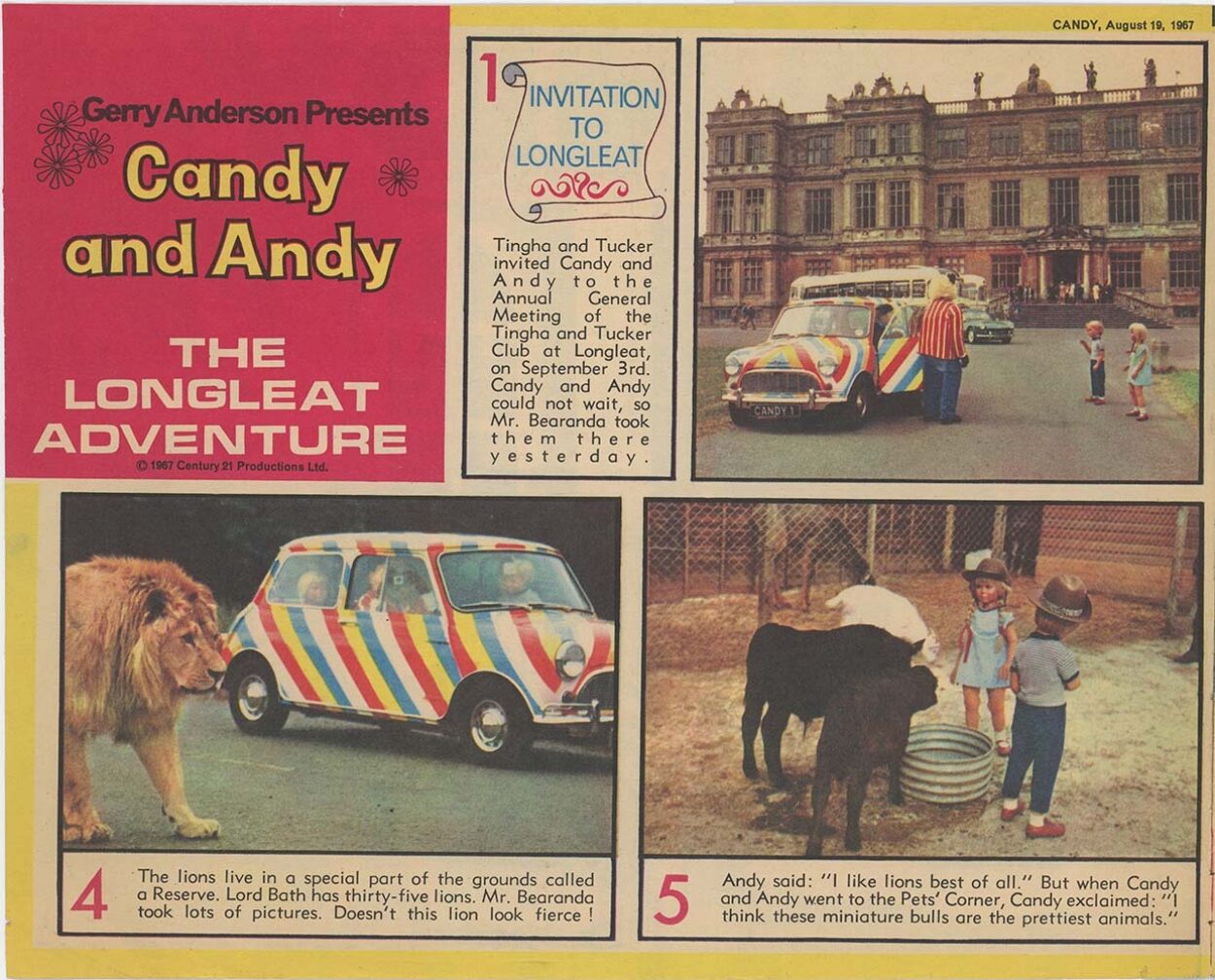

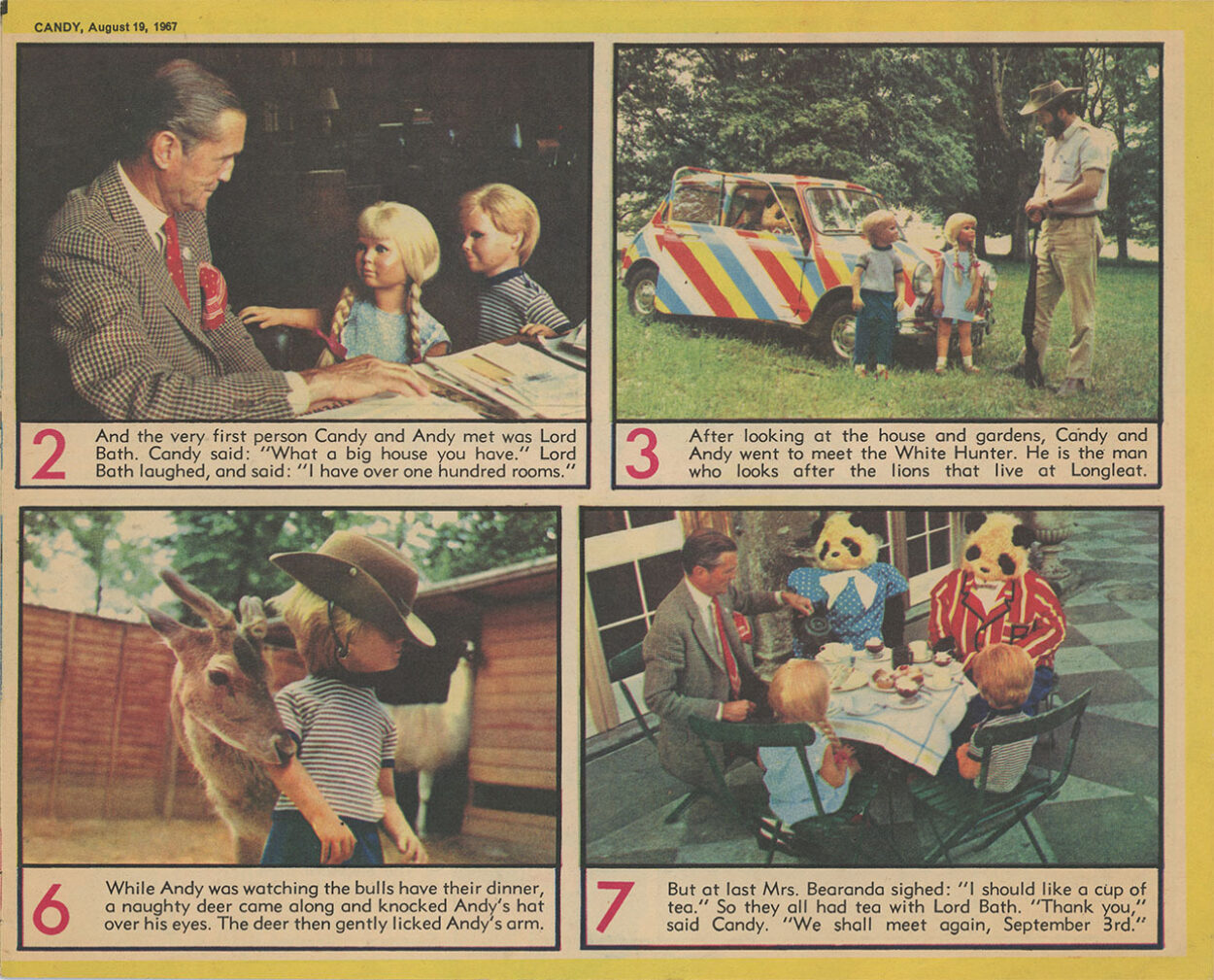

So along came Candy. In issue #1, Candy introduces herself. In the speech bubble she tells us ‘I am Candy. I live in the magic toy shop with my brother Andy and Mr. and Mrs. Bearanda…’. What is vital to clarify at this stage is that the Candy and Andy comic strips are not drawn in the traditional manner since the 19th century days of Ally Sloper, but are created with sequential photographs. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be talking about Candy and her family, almost sixty years on. They’d be just another set of characters in the jam-packed universe of literature and story books for children. Most of the adventures in Candy are domestic accidents, shopping, flying kites, trips to the countryside. The doll children can communicate with their toy friends, passing ducks or squirrels, and of course, real-life children. Indeed, the most disarming imagery in Candy is the presence of real people. Farmers, fishermen, vicars, petrol pump attendants, and even the Marquess of Bath at his stately home in Longleat turn up within the pages. So why unleash this oddity on the nations pre-schoolers?

When I spoke with Gerry Anderson at his office in Pinewood Studios back in December 1993, even he admitted that he was slightly hazy about the origins of Candy, but he recalled what was going through his mind at the time: ‘Instead of writing a story and having it drawn, I thought that it would be a great idea to produce the story photographically. Use 3D imagery, and presenting the real world in photographic form as a story’.

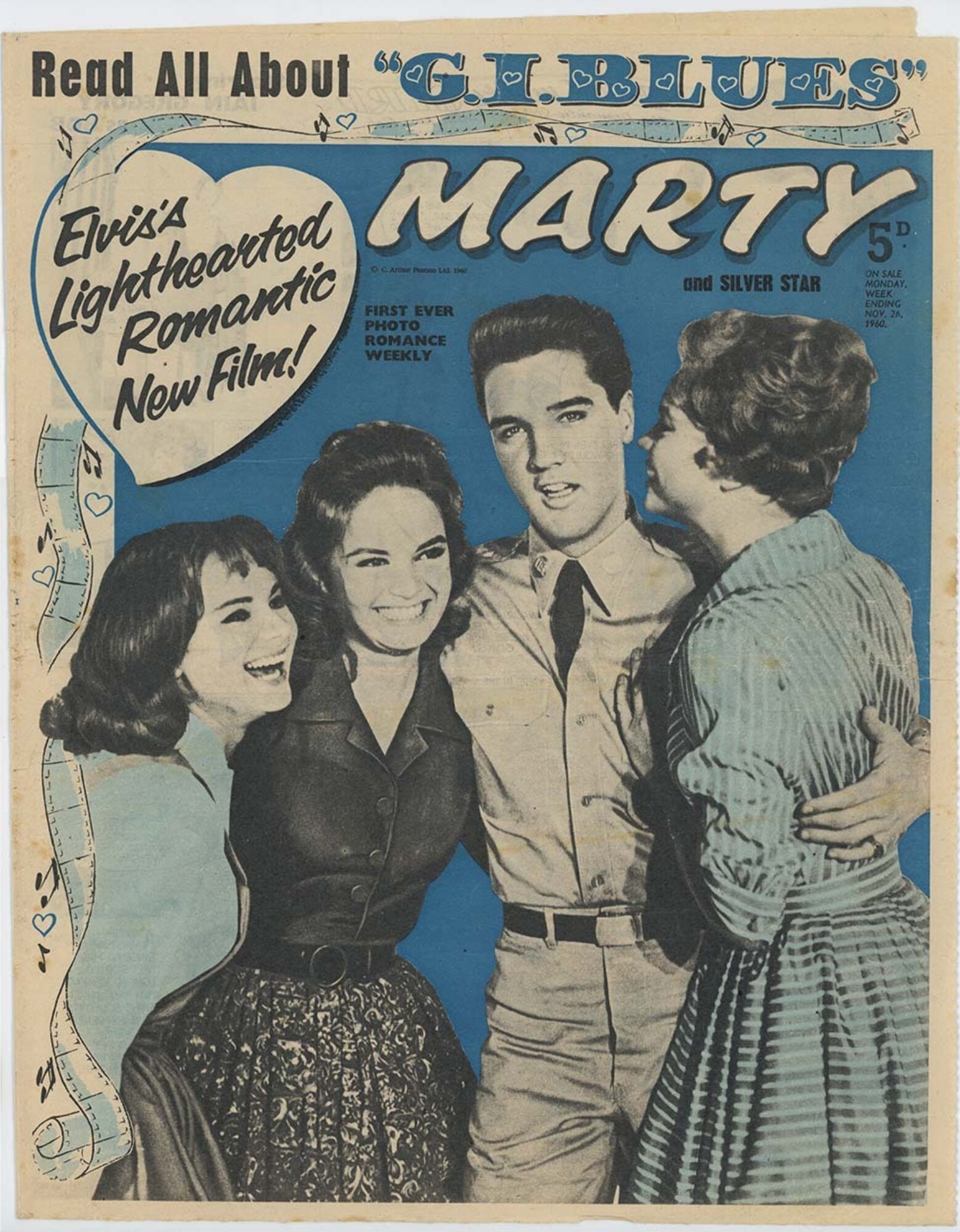

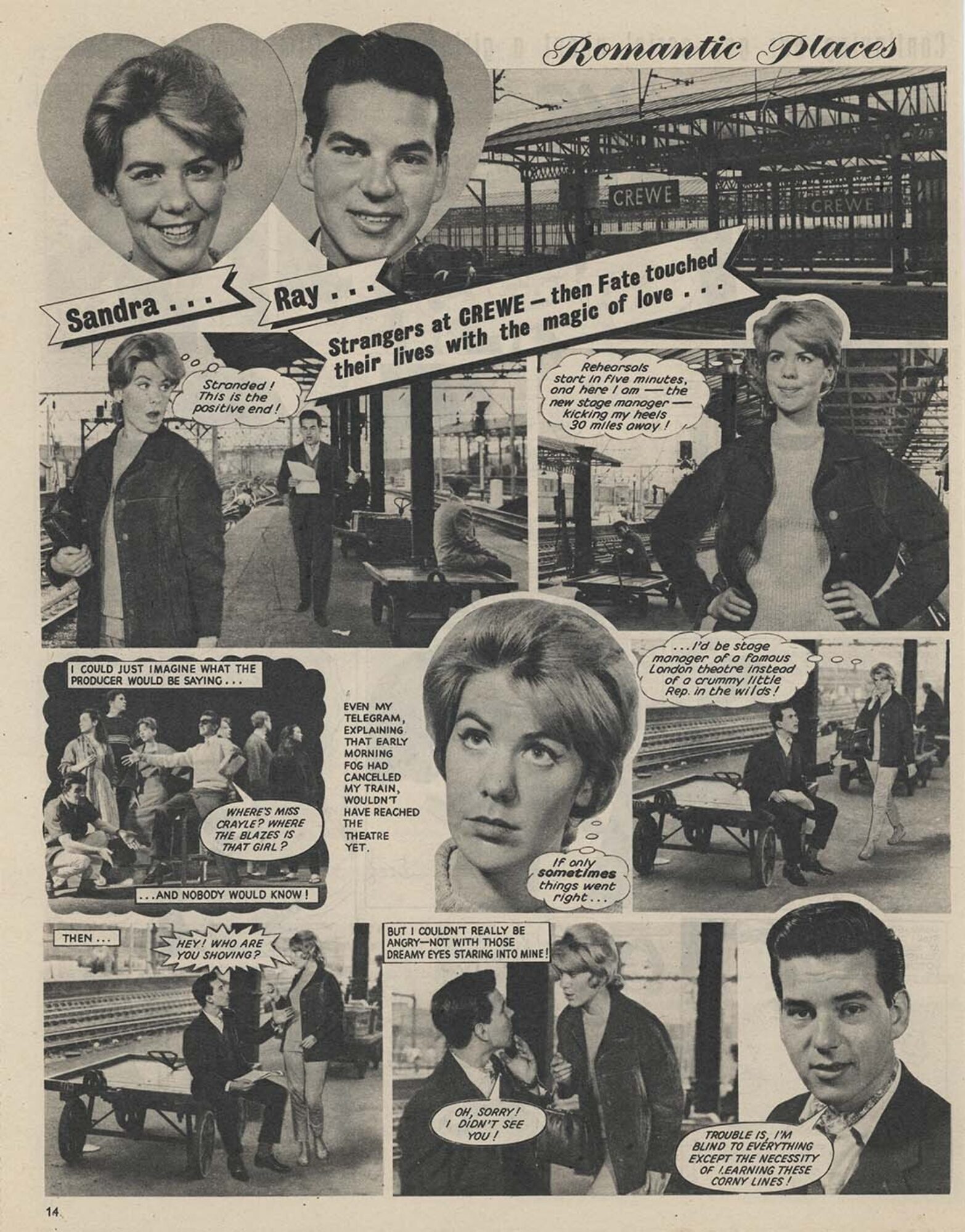

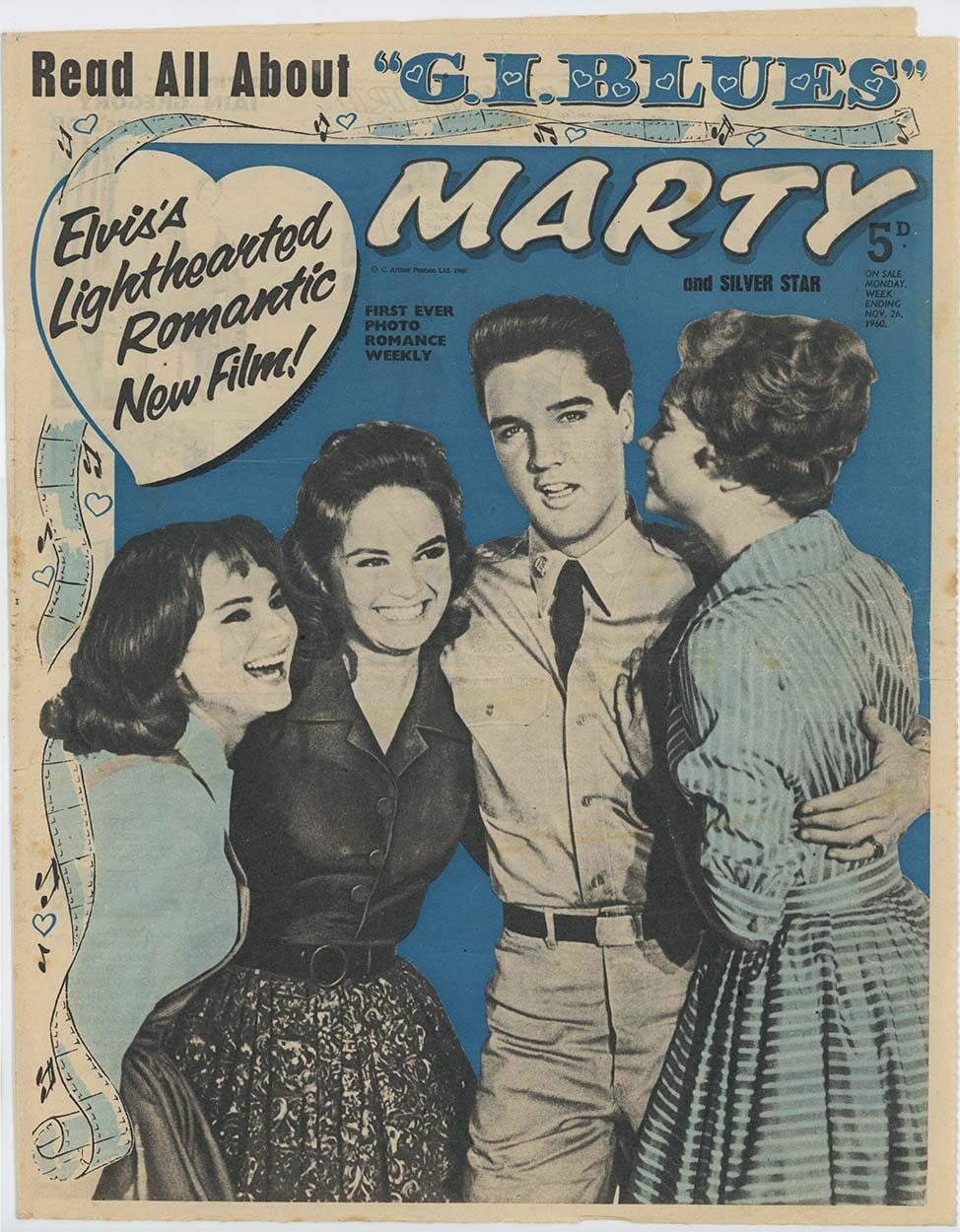

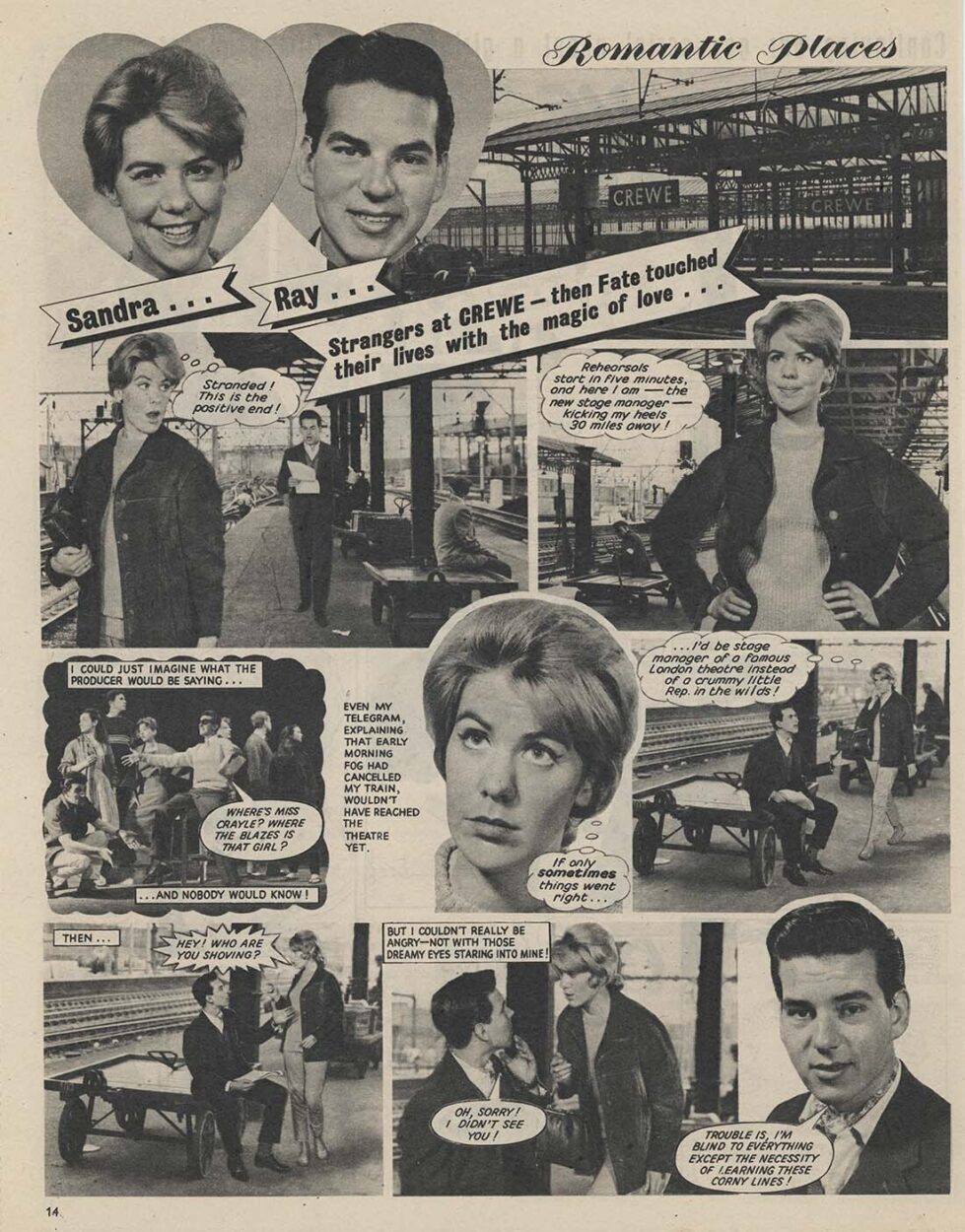

This kind of sequential storytelling format was in fact, not that novel at all. Emerging from post-WW2 Italy, the romance photo-story magazines known as ‘fotoromanzi’ mushroomed in a whirlwind era for film, fashion and magazine culture. Juggling a heady dose of glamour and relationship-fuelled melodrama, their popularity spread across Europe, South Africa and South America. In 1960 several photo-story titles appeared on the UK market. One was called Photo Romances - romantic picture stories told in real photos, and then there was Marty, named after the heart throb pop singer Marty Wilde, which was dubbed ‘the first ever photo romance weekly’. Marty was aimed at a younger teenage market than Photo Romances, and combined fashion tips, comic strips, show-biz gossip and meticulously constructed photo-stories: like the series ‘Romantic Places’ which could be set ‘in your home town’. Working on Marty at this time were Gillian Rowe and Angus Allan. Just like a story from their own fantasy photo strips, they got married, and continued to share a career in the comic book industry. Both would become instrumental contributors to the TV Century 21 family, and surely as the editor of Lady Penelope comic, Gillian Allan’s time on Marty must have fed into the photo-strip element that was the essence of Candy?

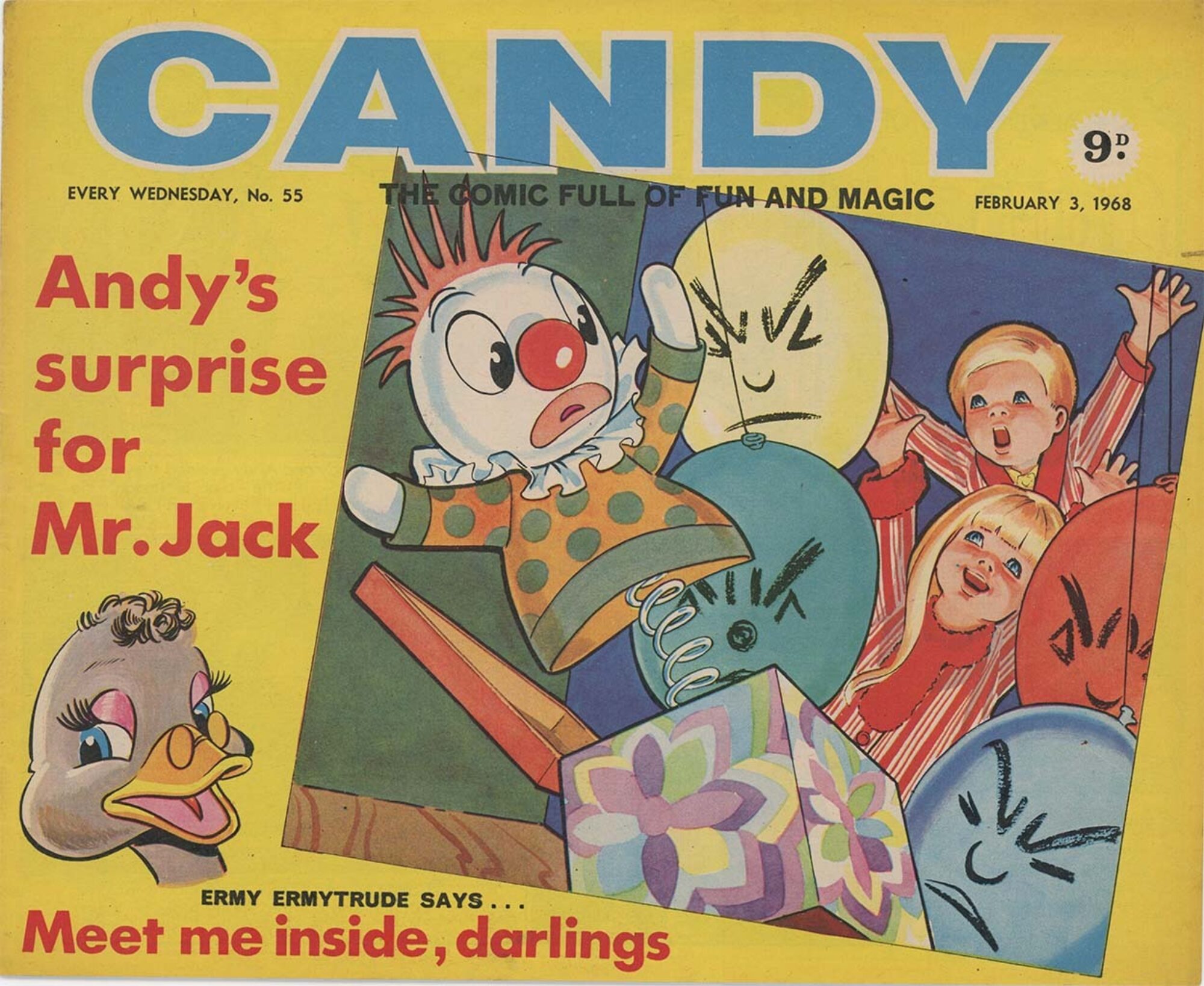

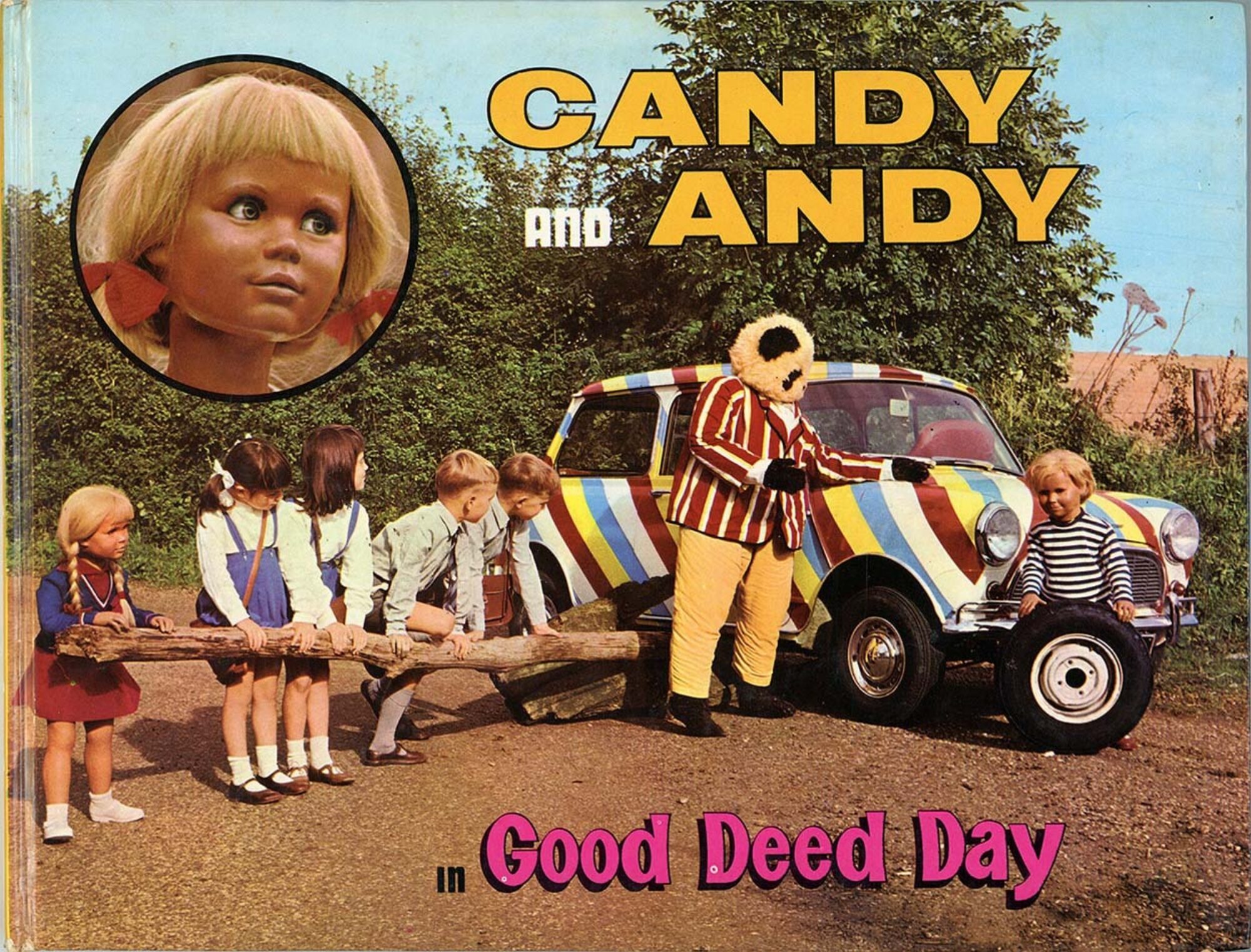

The weekly adventures of Candy and her Riverdale family and the puzzle pages were initially depicted by Doug Luke, who was one of the Andersons’ most trusted stills photographers. He was charged with a special new studio at Century 21’s Slough HQ, crammed with a dozen sets, two assistants, plus Stripey, a real D-Reg pop art styled Mini. However, in June 1967, after the first 20 issues there was the first sign that something was amiss. Firstly, priced at 9d, Candy was the most expensive comic around. It cost 2d more than TV21 and Lady Penelope, or its competitors like Jack & Jill, Bimbo or Pippin. After number 20, Candy switched printers (but not the price) with a resulting decline in the paper quality. It was clear that the initial promise of a slick full-colour comic crammed with photography couldn’t be sustained. The opening three-page photo story would become a two pager, and by 27 January 1968 when Candy #54 was issued, it was all over. The comic re-appeared the following week, but in name only. From then on until the end of the 1960s, shorn of the photos, Candy and Andy had morphed into genteel yet ordinary illustrated comic characters for younger readers.

Candy, Andy and the Bearandas then re-emerged in 1968 as a series of hard-backed story books. Unlike the two photo annuals that were published for the Christmas market which traditionally replicated the style of the comics, these new publications merged the photographic element within the look of a typical children’s story book. In charge of the production was Century 21 Publishing’s art director Roger Perry who took the dolls with him to his family home in Flamstead, Hertfordshire. In the titles Candy and Andy and the Magic Slippers, Candy and Andy and the Duck who could not Swim, Candy and Andy in Good Deed Day and Candy and Andy in a Penny for the Guy, Roger Perry constructs a unique and captivating documentary-style portrait of Flamstead and its neighbouring locality played out by dolls with real locals as the supporting cast.

Somehow then, after all the inventiveness, the storyboarded photo shoots where massive dolls needed to be cleaned-up after a tumble in a muddy river bank, dragging Candy, Andy and the Bearandas in and out of Stripey the Mini, this whole remarkable project slipped through the cracks of history for a long, long time. However, it was the photo-story that would make an unexpected return. This time to enjoy its most successful run ever. Riffing to a backdrop of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, romance in photos was being dished out by the publishing houses. How could a teenager in the late 1970s and 1980s not have a copy of Secret Love, Photo-Love, My Guy, Blue Jeans Photo Novels, or the legendary Jackie folded into their back pockets? That is another story, for another time…